Malines to Auschwitz

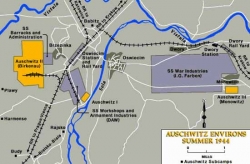

the deportation route taken by Perla and Michel. Auschwitz was never bombed by the Allies.

One veteran US pilot told Yad Vashem that he flew over the camp off-route and could, if so ordered, have easily and accurately dropped his bombs on the apparatus of death.

No such order was given. At any time.

Auschwitz and the railways were never earmarked as a target.

In a report entitled "Resettlement of Jews," SS-Stunnbannfuhrer Gricksch provided the following infonnation.

The

There, the Jews are unloaded and examined for their fitness to work by a team of doctors, in the presence of the camp commandant and several SS officers. At this point anyone who can somehow be incorporated into the work program is put in a special camp. The curably ill are sent straight to a medical camp and are restored to health through a special diet. The basic principle behind everything is: conserve all manpower for work. The previous type of "resettlement action" has been thoroughly rejected, since it is too costly to destroy .

WHAT THE SOLDIER SAW

"There was a

sign 'to disinfection'. He said 'you see, they are bringing children now'. They opened the door, threw the children in and closed the door. There was a terrible cry. A member of the SS climbed on the roof. The people went on crying for about ten minutes. Then the prisoners opened the doors. Everything was in disorder and contorted. Heat was given off the bodies, which were loaded onto a wagon and taken to a ditch. The next batch were already undressing in the huts. After that I didn't look at my wife for four weeks."

From the testimony of SS private Boeck (Langbein, quoted in Pressac, 181)

Who, then, did all of this?

Hitler's Willing

Executioners by Jonah Goldhagen

(They could have abstained)

Without comment of our own,we reproduce here a review of the historian's book, by novelist Patrick Quinn.

In 1941, Adolf Hitler's

That the government of a civilized nation could not only undertake but successfully conclude such a nightmarish policy without encountering significant domestic social opposition, particularly in a country as politically literate as was Germany, is one of the great puzzles of twentieth century European history.

Daniel Jonah Goldhagen has solved it. He has the temerity to suggest in this remarkable book that the Germans killed the Jews because the Germans wanted to.

The existing explanations for the ease with which the Nazis conducted their hellish program are varied, but to a greater or lesser degree almost all scholarly and popular interpretations of the Holocaust incorporate among their premises that it was am aberration, covert and uniquely efficient. The slaughter is said to have expressed the will of a small circle of lunatic Nazis and not the will of the Gertnan people, who were anti-semetic but not murderously so. It is said that the killing was conducted out of the sight of the nation and with industrial efficiency by a relatively small number of people insane with ideolQgy.

The effect of these premises is to make the Holocaust a political and not a social event, with the happy consequence that responsibility for it rests squarely on a small number of identifiable political and military operatives and not on the German nation as a whole.

In the years since the war, a great deal of intellectual firepower has been devoted to examining these premises, and and hopeful scholars have found some evidence in support for each of them.

Goldhagen, a professor government and social studies at Harvard, will have none of it."

Hitler's Willing Executioners" is a 620-page scholarly triumph written with white-hot rage and is the most important public reassessment of German social responsibility for the Holocaust since the

Goldhagen crushes the conventional interpretation under an avalanche of documentary data and argues that the destruction of European Jewry was a predictable consequence of Germany's widespread and virulently homocidal antisemitism, which was a fixture of the German social landscape long before the fall of the Weimar Republic. He concedes the industrial nature of the killing but suggests that, like all industrial activities, it involved a great many people rather than just a few, and that those people should be viewed primarily not as Nazi robots but as ordinary German men and women.

Goldhagen acknowledges that the regime did not especially publicize the killings, and so some Germans when they arrived in the East were surprised to find that their country was making good on its many threats to "solve the Jewish problem," but he demonstrates that once over that surprise most Germans assigned to the killing went at the work with enthusiasm.

Germans killed Jews in a variety of ways, although the notorious extermination camps in

Police battalions, auxiliary military units used to maintain order in occupied territory behind the lines, shot Jews by the hundreds of thousands; Goldhagen demonstrates that they were manned for the most part by utterly ordinary Germans who thought the shootings a difficult but unexceptional part of their duties.

Personnel attached to the police battalions were periodically rotated home, and so knowledge of the killing was widespread within

Contrary to the popular image, most of the men pulling the trigger were not highly indoctrinated SS race warriors. They were instead German men not physically suited for front-line duty, men in their 30s and 40s who ended up in police battalions because the duty was less rigorous than combat duty.

Goldhagen documents repeated instances in which unit commanders offered their men the opportunity to opt out of the killing but finds few soldiers who accepted the offer. Those who did almost always told postwar interrogators that they did so because of the gore factor: their spirits were willing, their stomachs weak. None, so far as the record shows, suffered significant punishment as a result of their decision.

There were only a handful of true extermination camps, but National Socialist

Goldhagen does not spend much time on this fascinating thesis; one hopes he will return to it at a later date.) As with the police battalions, available information on most of the camps does not provide evidence that they were a notably unrepresentative selection of the general body of German men and women in arms.

Goldhagen examines the management practices within the so-called "work camps," where prisoners were at least nominally expected to perform labor useful to the Reich. Non-Jewish prisoners often did so and were valued accordingly. The work camp at Mauthausen produced armaments that by the autumn of

1943 were vital to the German war effort, and so by November-December of that year the camp's monthly mortality rate for all non-Jewish prisoners had dropped to below three percent.

The monthly mortality rate for Jewish prisoners during the same period was 100 percent.

Goldhagen closes his fiery indictment with an immensely valuable examination of the schizophrenic forced marches inflicted upon camp inmates in the closing days of the war.

He again finds overwhelming evidence of vile behavior practiced programmatically by everyday Germans, behavior that was in many cases not directed from any higher authority, behavior that can only be called, in the argot of the social sciences, "voluntarism": with the Red Army only a few kilometers away and in the absence of any direction from a superior military authority, ordinary Germans marched helpless Jews around the countryside for no visible reason whatsoever until the Jews died.

Goldhagen's book is not perfect. For the acknowledged purpose of delimiting his argument (and to keep his manuscript at a manageable length), he does not discuss in detail the antisemitism or barbarous behavior of the many non-German national groups who tripped over one another in their rush to join the killing.

That list is long, and ranges from Slavic military auxiliaries who slaughtered Jews despite the fact that they themselves were regarded by Germans as "subhuman" to those elements of French society that shamefully collaborated in the collection and deportation of French Jews. His focus leads him to treat the odious antisemitism of central

Goldhagen is quite correct in asserting, however, that only in Germany did this hallucinatory mass antisemitism become sufficiently ingrained in the body of the population so as to constitute the foundations of a large-scale and obviously popular program of political action by the national government.

The lethal litany of anti-Jewish laws and public pronouncements that characterized Nazi governance during the 1930s - a period often overshadowed by the horrors that followed--were enthusiastically adopted by the mass of the German people. Goldhagen calls the attendant just-short-of-murderous mindset "eliminationist antisemitism," and points out that had the Germans not killed a single Jew after 1939 their government of the 1930s would nonetheless be remembered as the most antisemitic in history.

Following the onset of war and the invasion of the

This is a book that demands and will receive the attention of the scholarly community. Goldhagen's aim is simple enough. He asks his colleagues to drop their tortured explanations intended to exculpate the mass of the German people and instead to simply "believe the evidence of their own senses."

One wonders if they will.

The stop-over, Malines - en route to Auschwitz.

Paula sent her message as she waited that day with the other victims - Perla and Michel among them.

Malines (the French name for the Belgian town of Mechelen) is in central Belgium. In the province of Antwerp, it lies halfway between Antwerp and Brussels. During the war, the population of the town was about 60,000. In 1942 the occupying German regime chose the old General Dossin de Saint-Georges Barracks, in the middle of the old town, as an internment camp for the Jews of Belgium and a transit point for deportations to the east. It was apparently chosen because of its central location and its convenient access to railway lines leading to the camps of Eastern Europe.

The barracks, situated between the banks of the river and the railway lines, consisted of a three-story building surrounding a large central courtyard. Chosen in the summer of 1942 as part of the preparations for the Final Solution, the camp was still not ready when the arrests began. So on 22 July 1942, when the first group of Jews were arrested in Antwerp at the railway station, they were taken to the camp at Breendonk and then, five days later, transferred to Malines. They were its first inmates. During the weeks that followed, other Jews arrived, having been issued with orders (25 July) to report there for work.

Once in the camp, the inmates were divided into different groups: the Transport-Juden - those marked for immediate deportation; the Z-Juden - subjects of countries that were German allies or neutral - some of whom were not deported; the Entscheidungsfalle - borderline cases, such as those in mixed marriages or the children of such marriages - who, after some time, were sent to the camp at Viel in France; and the S-Juden - the politically "dangerous" - who were transferred to prisons or penal camps. Towards the end a number of gypsies were also held in Malines.

The conditions in the camp changed as time went by. The appalling physical conditions which existed under camp commander Philippe Schmidt improved when he was replaced, but there was constant abuse and hunger.

(Dr Pnina Rosenberg)

Evidence from Eichmann and others who took the decisions.

In Vichy France it was Abetz, Hitler's Ambassador, who first proposed measures against the Jews as early as August 1940. But Heydrich, jealous of the authority of the RSHA, immediately demands that the Security Police unit in the country be brought in (T/388). In fact, the handling of Jewish affairs is handed over to Advisers from the Accused's Section, first Dannecker, and then Roethke and Brunner. The first document written by Dannecker, in T/389, is dated 28 January 1941 and contains a proposal to set up concentration camps for Jews of foreign nationality, of whom there were many in France.

Indeed, we see that in October 1941 over seven thousand Jews had already been placed in the concentration camps of Drancy, Pithiviers and Beaune-la-Rolande, most of them stateless Jews. In a memorandum dated 22 February 1942 (exhibit T/400), Dannecker describes the continuation of preparations for evacuation, with the help of the Judenpolizei of the Vichy Government and stresses the central role which he demands for himself in all activities against the Jews of France.

On 11 June 1942, a consultation was held in the Accused's Section in Berlin, attended by the Advisers on Jewish Affairs in Paris, Brussels and The Hague. It was decided that the evacuations would include 15,000 Jews from Holland, 10,000 from Belgium and 100,000 from France (including the unoccupied territory) - see T/419. Dannecker prepares detailed instructions concerning the categories of Jews to be evacuated, and methods of carrying out the evacuation (T/425, dated 26 June 1942).

On 1 July 1942, a conversation takes place between the Accused and Dannecker, in which Himmler's order for the evacuation with all speed of all Jews from France is mentioned. There will be no difficulty in implementing the evacuation in the occupied part of France, but when it comes to the unoccupied part, the Vichy Government begins to make difficulties; therefore pressure must be put on it. In the meantime, transports will begin from the occupied territory. The proposed rate of three weekly transports of one thousand Jews each is to be increased considerably within a short time (T/428). Dannecker continues preparations for transports to Auschwitz (T/429) and agrees with representatives of the French police that the latter carry out, on 16 July 1942, a round-up of thousands of stateless Jews in Paris for the transports (T/440). On 1 July 1942, Dannecker fixes the places from which the first transports will be dispatched (minutes, attached to T/429, of a conversation with the Security Police officials).

The first train was due to leave the city of Bordeaux on 15 July, but it transpired that not enough Jews had been made ready to fill this train. Therefore, the Paris office cancelled the train (T/435). This enraged the Accused, as is evident from document T/436, which was signed by Roethke and is worthy of quotation, as evidence of the Accused's driving power and his status in the eyes of his subordinates:

On 14.7.42...SS Obersturmbannfuehrer Dr. Eichmann, Berlin, telephoned. He wanted to know why the train scheduled for 15 July 1942 was cancelled. I answered that originally the `wearers of the Star' in the provincial towns as well were to be arrested, but because of a new agreement made with the French Government, only stateless Jews were to be arrested in the meantime. The train scheduled for 15 July 1942 had to be cancelled, because, according to information received from the SD unit in Bordeaux, there were only 150 stateless Jews in Bordeaux. Because of the short time at our disposal, we could not find other Jews for this train. Eichmann pointed out that this was a matter of prestige.

This matter had necessitated drawn-out negotiations with the Reich Ministry of Transport, which had been successfully concluded, and now Paris caused the cancellation of the train. A thing like this had never happened to him. The whole business was 'disgraceful.' He would not inform Gruppenfuehrer Mueller of this at once, in order not to disgrace himself. He would have to consider whether France should not be dropped altogether, as far as evacuation was concerned. I requested that this should not be done and added that it was not the fault of our office if this train had had to be cancelled...the following trains would leave according to plan."

And indeed, the trains left, although the arrests did not bring the desired results (T/445), and on 3 September 1942 a report was submitted, showing that, up to that date, 27,000 Jews had been evacuated, of them 18,000 from the occupied territory and the remainder from the unoccupied territory (T/452).

Notice of each transport was sent to the Accused's Section and to the place of destination. Many such reports were submitted to us (T/444, T/447 (1)-(18), T/455, T/457, T/461, etc.), which refer to the period from July 1942 to March 1943. Most of the transports were directed to Auschwitz, and in such cases notices were sent to the Accused's office, to the Inspector of Concentration Camps in Oranienburg, and to the Auschwitz camp. A number of transports were sent "in the direction of Cholm" (for instance, T/1421, T/1422), which was a railway junction near Lublin, and in these cases the notices were sent to the Accused's Section and to Commanders of the SD and Security Police in Cracow and Lublin.

We heard the testimony of Professor Wellers (Session 32, Vol. II, pp. 579-591), who was arrested in December 1941, held at the Drancy camp from June 1942, and sent on to Auschwitz in June 1944. He described the round-up of the Jews and the expulsion from the Drancy camp to the East. An especially horrifying chapter was the expulsion of 4,000 children, separated from their parents and sent off to extermination, accompanied by heart-rending scenes described to this Court by the witness. In the documents, this chapter is reflected in an enquiry from Dannecker to the Accused on 10 July 1942, asking what was to be done with these 4,000 children (T/438). On 20 July 1942, Dannecker makes notes of a telephone conversation between himself and the Accused (T/439):

"The question of the deportation of children was discussed with Obersturmbannfuehrer Eichmann. He decided that, as soon as transports could again be dispatched to the Generalgouvernement area, transports of children would be able to roll" (Er entschied, dass sobald der Abtransport in das Generalgouvernment wieder moeglich ist, Kindertransporte rollen koennen).

On 13 August 1942, Guenther, of the Accused's Section, sends a cable (T/443), saying that the children can be included in the transports to Auschwitz.

In France, as in other countries, the Germans acted as it is written: "Thou hast murdered, and thou hast also inherited." The looting of the victim's property was carried out here by a special unit, set up for this purpose by Alfred Rosenberg (see report T/508 and the evidence of Professor Wellers, who was employed by the Germans in this unit - Session 32, Vol. II, p. 588). Nor did the Accused leave out the Jews who escaped to the Principality of Monaco in Southern France. His Section requested the Foreign Ministry to intervene with the Government of Monaco, so that the latter extradite the Jews from that territory (exhibits T/492-495).

According to a summary dated 21 July 1943, the number of Jews evacuated had increased to 52,000 (T/488). Two factors hindered the speeding-up of evacuations: (a) Collaboration by the Vichy Government in evacuating Jews of French nationality became halfhearted; (b) the Italians refused to collaborate in the part of Southern France they had conquered, and even permitted Jews to find shelter in territories occupied by them. The Accused's Section and his representatives in France went to some trouble to remove the obstacles. (See, for instance, exhibit T/613 - a letter marked IVB4, signed by Mueller, mentioning current negotiations carried on by the Accused with the German Foreign Ministry to put an end to interference by the Italians.)

In connection with Belgium, it was planned, as already stated, in the Accused's office on 11 June 1942 that 10,000 Jews be evacuated (T/419). On 1 August 1942, the Accused instructed the representative of the Chief of the Security Police and the SD in Brussels (Ehlers, who was the first Adviser on Jewish Affairs in Belgium) to evacuate stateless Jews (T/513). By 15 September 1942, 10,000 such Jews were evacuated. By 11 November 1942, the number of those evacuated reached 15,000 (T/515). A decisive date in the fate of the Jews of Belgium was the night of 4 September 1943. In the plan for action of the Security Police for a round-up to be carried out that night (T/519), it is stated:

"On the night of 3-4 September 1943, a large-scale operation will be carried out for the first time for the seizure of Belgian Jews, for posting to the East (Osteinsatz), as required by the Head Office for Reich Security."

In the Belgian Government's report (T/520), the round-up is described as follows (p. 28):

"At first, the hunt affected only Jews of foreign nationality. Belgian Jews could believe at that time that they would never be molested. A promise to this effect was made by General von Falkenhausen...on the initiative of Queen Elizabeth, who was supported by Cardinal van Roy. In spite of these undertakings, on the night between the 3rd and 4th of September 1943, Gestapo men and Flemish collaborators broke into the apartments of Belgian Jews in Antwerp and removed them forcibly from their homes, to be taken in trucks to the Dossin barracks in Malines. From this date onwards, there began the Jew-hunts all over the country, although the pace was slower in Brussels, because there the Gestapo did not have the same influence upon the other German administration services as they enjoyed in other places.

(The trial of Adolf Fichmann - the Nikor Project)